December 18, 2007. Vol. 1, No. 8.

State Development Fund Rewards Hype:

Incentives Great, Penalties Few For Companies That Overstate Their Benefits

Texas Governor Rick Perry uses the publicly financed Texas Enterprise Fund to pay companies to invest in the state and create new jobs here. At a time when both liberals and conservatives question the practice of doling out public dollars to private enterprises, the Enterprise Fund has awarded $233 million—almost two-thirds of its total grants—to companies that subsequently announced layoffs of some Texas workers or failed to create the number of jobs that they had promised in exchange for public funds. Penalties assessed on companies who don't meet their employment goals are weak at best and sometimes companies can escape penalties altogether.

The governor’s four-year-old Enterprise Fund, along with its sister project, the Emerging Technology Fund, are facing growing public scrutiny. Last month Speaker Tom Craddick announced that the House Committee on Economic Development would conduct a review of the program’s effectiveness. “Some of the goals [of the projects] aren’t being met, but at the end of the day these companies don’t have penalties. They get a free ride,” says Corpus Christi Rep. Solomon Ortiz, Jr., who requested that the committee conduct the review. “We have to make sure we are good stewards of taxpayer dollars.” The committee will make recommendations to the full legislature in 2009.

Enterprise Fund recipients receive all or part of their grants upfront. The state can force a company that fails to meet its job-creation targets to repay some funds. But these “clawbacks” lack teeth. To date the state has enforced clawbacks on just three companies, which collectively have returned less than one percent of their Enterprise Fund awards. The absence of serious penalties creates incentives for companies to exaggerate the benefits that they offer the state in order to maximize the public funds that they receive.

Program oversight also is inherently problematic. The governor’s office appears to have a major political interest in portraying the Enterprise Fund as a success, a role that conflicts with its ability to safeguard the funds and penalize lackluster awardees. Some Enterprise Fund contracts, for example, require grantees to consult with the governor’s office before issuing press releases related to their investments or employment in Texas. Many Enterprise Fund agreements contain annual job-creation targets that start low and increase incrementally over the life of the agreement. If an Enterprise Fund recipient outperforms its low job targets in early years, the program awards it job credits that the grantee can use in future years if it fails to add Texas jobs or if it lays off Texas workers. |

|

The recent meltdown of U.S. housing markets raises new questions about how wisely these tax dollars have been invested. The Enterprise Fund awarded $35 million in state funds to two of the nation’s leading subprime mortgage lenders: Countrywide Financial and Washington Mutual. Subprime mortgage lending, also known as predatory lending, initially targeted borrowers with bad credit or shaky finances. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that, by 2005, lenders steered 55 percent of all subprime mortgages to people who could have qualified for conventional loans on much better terms.1 Many of these borrowers will lose their homes as payments spiral beyond their means.

Reeling from their hemorrhaging loan portfolios, both Countrywide and Washington Mutual already have announced massive layoffs nationwide, with some affecting Texas. It is unclear when either troubled company will hit bottom. The Enterprise Fund awarded almost 10 percent of its grants to major predatory lending companies. It would have handed out even more tax dollars to this sector if Ameriquest Mortgage had not declined Enterprise Fund overtures in 2004. By contrast, state pension funds have limited their exposure to this risky sector.2

Governor Perry urged the legislature to create the Texas Enterprise Fund in 2003 by tapping the “rainy-day fund” that the state sets aside for hard economic times—such as those that now may be coming thanks to the subprime-mortgage craze. The governor promised that the Enterprise Fund would be used to “aggressively” attract employers to the state. The governor’s office continues to oversee the program, with the lieutenant governor and House speaker also approving all Enterprise awards. To date, they have doled out $359 million to 38 recipients.

Declawing the Clawbacks

Enterprise Fund grantees are subject to certain penalties if they fail to meet their annual job-creation requirements. These clawbacks can include returning a specified amount of state funds for every promised job that they failed to provide and forfeiting any additional state funds that they had yet to receive. To date the state has invoked clawbacks against just three of the 38 Enterprise Fund grantees: Cabela’s, Hilmar Cheese and the Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine. Even in these cases, however, the three companies have kept almost all of the $54.4 million that they collectively received, with the state recovering less than two-tenths of one percent of the funds it invested in these lackluster projects.

Enterprise Fund Clawbacks

| Grantee (Deal year) | Jobs Pledged |

State Funds Disbursed |

Clawback Amount |

Share of Money Returned |

| Cabela's (’04) | 400 |

$400,000 |

$70,384 |

17.60% |

| TX Inst for Genomic Medicine (‘05) | 5,000 |

$50,000,000 |

$16,905 |

0.03% |

| Hilmar Cheese (‘05) | 1,962 |

$4,000,000 |

$9,770 |

0.24% |

TOTALS |

$54,400,000 |

$97,059 |

0.18% |

The Enterprise Fund agreement with Cabela's requires creation of only 400 jobs.

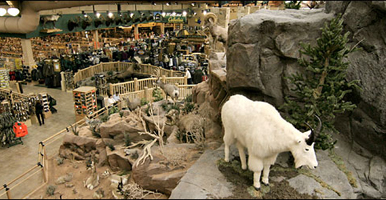

The state invoked its largest clawback against Cabela’s. The Enterprise Fund awarded this sporting-goods chain $600,000—with $400,000 paid upfront—for pledging to create a total of 400 jobs at two stores in Buda and Fort Worth by December 31, 2005. If Cabela’s fell short of its 400-job target, its contract requires it to repay the state $332 for each job that it falls short—for every year through 2009. By contrast, the incentives contracts that local governments awarded to Cabela’s for its Buda store required the company to repay $5,000 for every missing job.3

The two new Cabela’s stores laid off 70 employees in November 2005,4 and the company ended that year 86 jobs short of its pledge.

The Cabela's store in Buda, Texas. Billed as a tourist destination, the store also includes an extensive taxidermy display. New York Times. |

As a result, Cabela’s forfeited the $200,000 of its grant that the state had not yet dispursed and it paid a $28,552 penalty for the 86 missing jobs. By the end of 2006, Cabela’s fell 126 jobs short and had to pay a $41,832 fine. The company could face additional fines at the end of this year. So far it has repaid $70,384, or 18 percent of the total state funds it received. |

The Enterprise Fund’s two largest grants were for $50 million each. One of these went to the Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine, a partnership between Texas A&M University and Lexicon Genetics (the Houston Chronicle revealed that some of Governor Perry’s top campaign contributors are major investors in Lexicon Genetics).5 The Institute received its state funds in a lump sum soon after the parties announced the deal in the summer of 2005.

The Institute contract includes separate job targets for A&M and Lexicon. Lexicon has struggled to meet its targets. Although it exceeded its initial job target by 30 jobs at the end of 2005, Lexicon created just 12 new jobs in 2006, falling 37 jobs short of its target. After applying the 30 job credits it earned the year before, Lexicon had to pay the state a $16,905 penalty for the seven remaining missing jobs ($2,415 per job). In this way, Lexicon created only 25 percent of its job requirements in 2006, yet it repaid just .03 percent of its Enterprise Funds.

At the end of 2005 the Enterprise Fund awarded Hilmar Cheese $7.5 million. By the end of 2006, the company had created just seven of the 17 jobs stipulated in its contract. Hilmar repaid the state a total of $9,770 for the 10 missing jobs, or just .24 percent of its $4 million grant.

Enterprise Fund Recipients

With Job Losses or Job-Shortfall Clawbacks

TEF Grant |

Company | Pledged Jobs |

Reported Layoffs |

Capital Investment |

Location |

$50,000,000 |

TX Instruments (with UT Dallas) | 1,000 |

424 |

$3,000,000,000 |

Richardson |

$50,000,000 |

*TX Institute for Genomic Medicine | 5,000 |

0 |

$45,700,000 |

Houston, College Sta. |

$40,000,000 |

Sematech | 4,000 |

80 |

$190,000,000 |

Austin |

$35,000,000 |

Vought (Aircraft Manufacturing) | 3,000 |

600 |

$598,000,000 |

Dallas |

$20,000,000 |

Countrywide Financial | 7,500 |

<12,000† |

$200,000,000 |

Richardson, Midland |

$15,000,000 |

Washington Mutual | 4,200 |

3,000† |

$50,000,000 |

San Antonio |

$8,500,000 |

Home Depot | 843 |

650 |

$809,170,000 |

Austin, New Braunfels |

$7,500,000 |

*Hilmar Cheese | 1,962 |

0 |

$190,000,000 |

Dalhart |

$5,480,000 |

Lockheed Martin | 800 |

400 |

$58,000,000 |

Houston |

$1,000,000 |

Raytheon | 200 |

100 |

$21,700,000 |

McKinney |

$600,000 |

Cabela’s | 400 |

70 |

$120,000,000 |

Buda, Fort Worth |

$233,080,000 |

TOTALS |

28,905 |

17,324† |

$5,282,570,000 |

†Includes nationwide layoffs, with an unknown share in Texas.

Note: A table provided by the Governor's office listed Cabela's job commitments at 600 jobs. The Enterprise Fund agreement with Cabela's requires creation of only 400 jobs.

Apart from the three grantees that have been subject to some sort of clawbacks, eight other companies have publicly announced Texas layoffs after receiving Enterprise Fund grants. While it is not known which—if any—of these companies suffered a net reduction in their Texas workforce, the layoff announcements are significant since not all employers publicize their layoffs. When combined with the three clawback grantees, these eight layoff companies consumed $233 million in Enterprise Funds, or almost two-thirds of the project’s total.

Subprime Enterprises

When Governor Perry announced a $20 million Enterprise Fund grant to Countrywide Financial in December 2004, the company had just become the nation’s No. 1 mortgage lender. Countrywide fueled its rapid growth through aggressive marketing of high-risk, subprime loans initially aimed at borrowers with less-than-perfect credit and financial conditions. Many of these mortgages featured low introductory payments and rates that later reset beyond means of the borrower. An estimated 2 million families will be foreclosed out of their homes before the subprime crisis bottoms out.

Countrywide lost almost 70 percent of its market value in the space of a year.6 To help prop up the troubled giant, the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta has loaned the company $51 billion, which accounted for 37 percent of this federally chartered bank’s outstanding loans at the end of September. Countrywide announced that month that it would layoff up to 12,000 employees, or 20 percent of its national workforce. Although this includes the shuttering of its Midland office that employed 100 people, Countrywide has not revealed how many layoffs will occur in Texas—where one in five of its employees work.7

Countrywide’s contract requires the company to create 7,500 new jobs in Texas, including 4,000 by the end of this year and 5,500 by the end of 2008. The company is supposed to repay the state $854 a year for every job shortfall. Yet it is unlikely to make such payments over the next few years. This is because the Enterprise Fund contract set such low job targets for Countrywide’s first years that the company has built up 4,000 job credits that it can apply to any future shortfalls. “Countrywide has far exceeded the interim annual targets under our agreement with the Texas Enterprise Fund, already creating great economic benefits,” a company press release quoted Countrywide CEO Angelo Mozilo saying last month. “At this point, we remain confident that we will meet the ultimate goal, as well.”

The Enterprise Fund also has awarded $15 million to Washington Mutual, or “WaMu,” the nation’s No. 3 mortgage lender. This lender’s stock has dropped 60 percent this year. WaMu also has leaned heavily on the Federal Home Loan Bank system for emergency funding, increasing its borrowing from these banks—which carry the implicit backing of the U.S. government—by $31 billion this fall.8 Predicting that home loan originations will plummet 40 percent in 2008, WaMu announced this month that it would abandon subprime lending and layoff more than 3,000 workers nationwide.9

Other Layoffs

Mortgage lenders are not the only Enterprise grantees that have announced Texas layoffs since the state paid them to create jobs here. Texas Instruments (TI) is the only company besides the Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine to land a $50 million Enterprise Fund grant. This 2003 grant was for TI to build a computer-chip factory in Richardson and create 1,000 new jobs. Although TI finished construction last year, the new plant remains empty. A spokesperson told the Dallas Morning News in September that the company intends to move equipment and 1,000 workers to the plant once its other facilities are running at capacity.10 Instead, TI announced the layoff this fall of 424 workers in the Dallas area.11

The Enterprise Fund’s third-largest grant—for $40 million—went to Sematech. This computer chip company promised to maintain an average payroll of at least 400 employees through 2011 and to spawn 4,000 jobs at other high-technology companies by 2014. Sematech announced the layoff of 80 of its 500 employees in early 2006. This May it announced that it was expanding operations—but that it would do so in Albany, New York. The company is negotiating to sell its Austin lab, which employs almost half of its workforce. If Sematech’s Texas payroll falls below 400 workers it will need to return around $30 million, or all of its state funds not dedicated to University of Texas research. The company must also create or attract 4,000 indirect technology jobs at employers other than Sematech or else the company will pay $10,000 per missing job.

The Enterprise Fund gave its fourth-largest grant to Vought Aircraft. In return, the maker of airplane parts agreed to create 3,000 new jobs by 2009 and to maintain a total of 6,000 Texas jobs for ten years. Two years after the state gave Vought $35 million in 2004, the company announced the layoff of 600 workers, or most of the employees of its Dallas plant.12 “It’s too soon to forecast what our employment levels will be in 2009,” a Vought spokesman told the Dallas Morning News at the time.

If Vought’s employment numbers fall short by 2009 it will be required to repay $1,000 per job. Starting in 2011, however, Vought’s contract allows it to claim credit for any jobs created at its suppliers that stem from Vought’s expansion. Giving grant recipients credit for indirect, supplier jobs greatly increases the potential for the kind of creative accounting that can defraud the Enterprise Fund.

After receiving Enterprise Fund grants, three other companies announced layoffs in Texas that did not directly involve their Enterprise Fund facilities. Home Depot, which received $8.5 million to create 843 jobs at central Texas data and distribution centers, closed two Dallas-area call center this year that had employed a total of 650 people.13 Lockheed Martin, which received almost $5.5 million from the Enterprise Fund to create 800 jobs at a Houston aerospace plant, laid off 400 Fort Worth workers in 2006. That same year, Raytheon, which received $1 million to create 200 jobs at an aerospace and defense plant in McKinney, laid off 100 El Paso workers.

Conclusion

Since its inception in 2003, the Texas Enterprise Fund has received almost $500 million in public funds. Governor Perry, who lobbied for the fund’s creation, largely oversees it, even as he politically promotes the Enterprise Fund’s image. The governor’s office keeps a tight rein on information about the fund’s job creation and economic benefits.

As currently designed, the Enterprise Fund sets low goals for job targets in the first years, allowing companies to stockpile extra job credits to expend on later shortfalls. In some cases, the fund also counts indirect jobs, which are harder to track and can lead to less accountability. Enterprise Fund contracts contain penalties for companies that don’t meet employment goals, but the penalties lack the teeth necessary to discourage companies from ramping up their initial estimates of their benefit to the state’s economy.

The public, state officials and the House Committee on Economic Development should seriously consider the wisdom of investing public funds in privates businesses at all. State funds might be more wisely invested in such structures as public education and public health, which arguably have more potential to help more Texans obtain employment and improve their quality of life. If the state decides to continue investing public dollars in private businesses, then the House committee should seek ways to establish more oversight outside the governor’s office and to impose stricter job-creation targets and harsher penalties for companies that do not deliver on their contracts.

Some will rob you with a fountain pen. - Woody Guthrie

Watch Your Assets is a Texans for Public Justice project.Lauren Reinlie, Project Director.

Endnotes:

1 “Subprime debacle traps even very credit-worthy,” Rick Brooks and Ruth Simon. Wall Street Journal, Dec. 3, 2007.

2 “Subprime slide only grazes state pension funds,” Robert Garrett. Dallas Morning News, Dec. 11, 2007.

3 “Cabela’s must repay incentives,” Molly Bloom. Austin American-Statesman, July 6, 2007.

4 “Cabela’s lays off 70 at new stores,” Virgil Larson. Omaha World-Herald, Nov. 11, 2007.

5 “Firm’s investors include donors to the governor,” R.G. Ratcliffe and Anne Belli. Houston Chronicle, August 7, 2005.

6 “Countrywide predicts revival,” David Mildenberg. Austin American-Statesman, Oct. 27, 2007.

7 “Countrywide, other benefactors of job fund lay off employees,” Kelley Shannon. Associated Press State & Local Wire, October 7, 2007.

8 “U.S. tosses lifeline to mortgage lenders using home loan banks,” Bloomberg News. Oct. 30, 2007.

9 “Washington Mutual to cut 3,000,” Dallas Morning News. Dec. 11, 2007.

10 “Empty TI plant earns tax breaks,” Staci Hupp. Dallas Morning News, Sept. 24, 2007.

11 “TI to cut 191 Jobs”, Associated Press Financial Wire. Sept. 10, 2007.

12 “Vought layoffs create political fallout,” Dallas Morning News, April 7, 2006.

13 “Home Depot closing call centers in Dallas, Chicago, Tampa,” Maria Halkias. Dallas Morning News, December 5, 2007.